Hello all,

Today I will talk about one of the most complicated costumes of Greece, that of the Karagounai. The Karagouni are an ethnic group which inhabit the lowlands of western Thessaly, just east of the Pindus mountains. They mostly inhabit villages in the area surrounding the cities of Trikala, Karditsa, Sofades and Palamas. Some villages in the area are still inhabited solely by Karagouni. They have retained their folk costume longer than many parts of Greece, many women wearing them daily well into the 20th cent. Today, a simplified form of this costume is popular with many Greek performing groups.

The origin of the Karagouni is unclear. Hatzimichali quotes several sources on this subject, which are rather muddled and which contradict each other. Some maintain that they are derived from Koutsovlachi, others flatly deny this; some claim that they are Arvaniti [Albanian], some that they are Hellene in origin. They seem to speak no language but an archaic Greek dialect. They were not nomads or pastoralists, but farmers who were tied to the land in a feudal type plantation system called Çiftlik under Turkish occupation. [If anyone has more information on this, I would appreciate being better informed]. Starting about 1889, they began to take ownership of the land which they farmed, as the feudal Çiftlik system began to break up.

The men wear the costume with foustanella or pants with no distinctive attributes, such as may be found over a large area of Greece and Albania.

The women's costume is, however very distinctive. The Karagouna, as the women are called, are famous for their beauty and grace. There is a very famous song about one such woman which is sung over much of Greece. The local women do a simple but graceful dance to this song in Thessaly. Another version of the song with a similar but distinct melody became popular further west, on the other side of the Pindus mountains in Epiros. This is the dance with three parts which the International Folk Dance community knows as 'Karagouna', after the name of the song. It is not done by the Karagouni themselves.

The original foundation garment is the chemise, pokamiso. Like in so many places in Europe, this term is now used to mean shirt. It has the same standard cut as is found in Macedonia and the Balkans. There is embroidery on the cuffs, around the neck opening, on the hem and along the seams on the outside of the sleeves and on the bottom part of the chemise.

There is also a solid row of tassels attached to the hem, and tassels on the sleeve ends which have spaces between them. Along with the amount of embroidery, the length of the tassels varies by district, and of course, pokamisa meant for more dressy occasions have more embroidery and longer tassels than those meant for more everyday occasions. The modern simplified stage version of the costume usually keeps the tassels but omits the embroidery, or replaces it with a simple band of black trim, which is a real shame.

Instead of making several chemises, the Karagounai would only make three, and then make several different sets of sleeves. The armholes would be finished so as not to ravel, and the sleeves would be basted into place for wearing.

Because the sleeves are open and somewhat full, wrist warmers of woven wool were developed to be worn under them. These later became knitted, and later still, became attached to an undergarment which covered the torso under the chemise. This development also occurred among the Sarakatsani and in many parts of Macedonia. In the Karagouna region this undergarment is called fanella.

Another recent development is the appearance of the trachilia, a dickey which covers the front of the chemise and can be embroidered or ornamented with printed cloth. This has also become popular among Macedonian costumes relatively recently. Sometimes the contrast of old, beautiful embroidery with tawdry tinselly modern cloth is distressing. Sometimes it is done more tastefully. Here is a woman from Karditsa in her dress outfit. She is wearing a trachilia of finely woven damask.

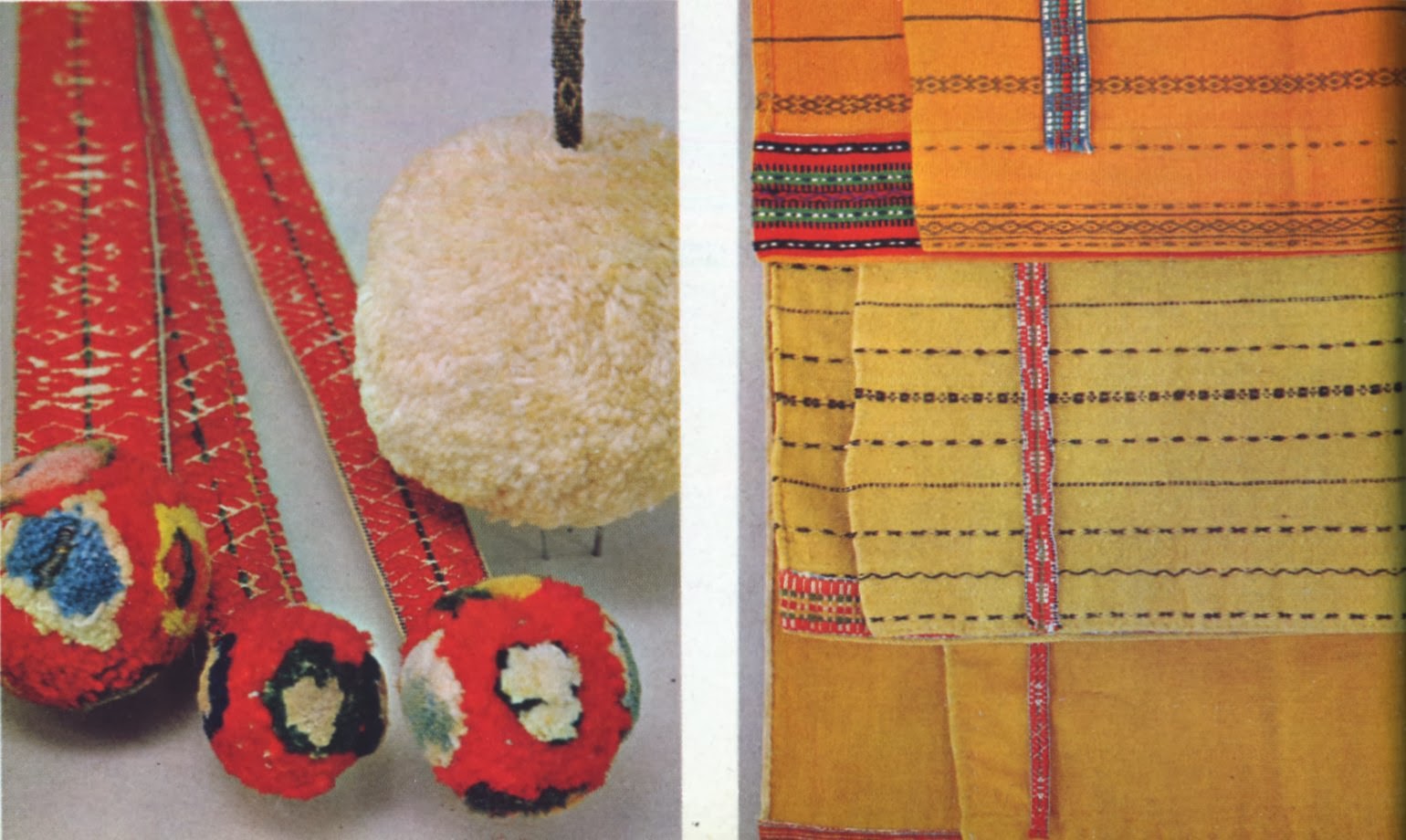

The next layer is a garment, or rather two garments, called saya. This is a sleeveless garment which is open down the front. It is worn in many places around the balkans. In the Karagouna costume, the lower part is pleated, and the bottom edge is decorated with cord embroidery.

In this photo just above, you can see that this woman is wearing two of them as is the original tradition. Here is another photo of a girl wearing a very plain everyday costume; you can see that she is wearing a pokamiso with limited embroidery, a plain apron and two sayas of different colors.

In the modern simplified costume, as in the photo at the head of the article, usually only one saya is worn. Here are a couple of examples of the embroidery on the hem of the saya. The colors used vary by location.

Here is one cut of the saya used in the Sofades region. The number of gores added to the sides varies, with more festive sayas being fuller.

Here are a couple of women from the Karditsa area wearing their festive summer outfits. You can see that the saya is made to fall in pleats at the sides. They seem to be wearing only one saya each.

In the Karditsa - Trikalia area, often the saya is made of a bodice and a full skirt. This is especially true of the two villages of Megala Kalyvia and Ayia Kyriaki, where the saya is made very full and falls in pleats all the way around.

In the area around Sofades and Palamas, the garment worn under the saya was not another saya, but another garment called kavadi, which has elbow-length sleeves, and is usually red, often of a dark shade. The kavadi is trimmed in gold braid and is worn as part of the summer festive costume.

In this photograph this woman is wearing a blue saya over a dark red kavadi in the Sofades - Palamas style.

The sleeves of the kavadi are a focus for ornamentation, especially gold couching and trim along the seam. These kavadomanika were greatly admired, so that in the areas which did not wear the kavadi, the sleeves were added to the costume separately. They are sewn to a small linen or cotton bodice which is worn under the outer saya. Here is an example of a bride from Rizovouni in the Karditsa region. You can see that she has the kavadi sleeves, but is not actually wearing a kavadi. On more formal occasions, as this woman above is doing, extra ornaments are added to the sleeves. Compare her sleeves to the entire kavadi shown above.

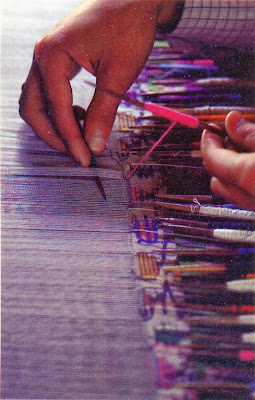

These separate decorative cuffs are called manikoulia and have a variety of different embroideries. This is another way of wearing a variety of ornamentation without making multiple garments.

These area attached with hooks and eyes. They are always narrower on the ends which lie under the arms for more ease of movement. The narrow ends are generally not visible when worn.

Finally, over the fanella, the pokamiso, the trachilia, the undersaya, the kavadomanika and the oversaya is worn a vest, called yilekia. This word is cognate to both the south slavic term jelek and the French term gilet. The yilekia is short, not quite reaching the waist, except for two tabs in front which are found in some regions and which tuck under the belt to hold it in place.

The yilekia is completely covered in cord embroidery except for a rectangle in back. Many of them have exquisite cordwork.

Two different aprons are worn with this costume, the podia and the mesa podia. If you peruse the various images in this article you will see that either may be worn, or ideally, both together.

The underapron, the mesa podia is made of silk, usually has embroidery on the bottom edge, and perhaps a flounce or fringe. This is an elaboration of the plain everyday apron seen above. It can be of almost any color, is longer than the saya and almost as long as the pokamiso.

The embroidery tends to be of a more modern satin stitch floral type.

Over this is worn the podia; on festive occasions by those who can afford one. It is covered with elaborate cord embroidery.

Very often, as here, there is a loop attached to one side on the top and a woven band on the other. The band is passed through the loop and the podia is held on in this manner. The range of ornament in various colors is remarkable. The amount of handwork on these makes them very expensive.

This type of apron is not found in any other Greek costume. But see this Vlach costume from Sqepur in Albania. This might give some insight into the origin of the Karagouni.

The traditional belt was woven and covered with the same kind of cord embroidery as is found in the rest of the costume, fastened with a large fancy metal buckle. Today this has been completely replaced with a belt all of metal, fashioned to match the buckle.

Hand knitted knee socks in white with red toes and heels are worn. These may include narrow, perhaps 1 cm wide stripes of knitted in or embroidered ornament. The traditional slipper shoes are called kordelia. Hatzimichali describes these as being of black calfskin, with laces in the front, a low back, with a thick low heel.

Today the Karagouni often wear whatever shoes they can buy, and folk groups tend to wear tsarouchia.

The old headdress consisted of a cap, skoufia, wrapped around with a linen cloth that had the same kind of embroidery and tassels on the end as the pokamiso. This was wrapped so that none of the white cloth showed when done.

Later the cap was replaced by a thick braid of goat hair called kothros.

Over this a kerchief was wrapped, with a woven or embroidered design in one corner and the edges nearby. Often additional brocade or other ornamental cloth was added to two edges.

The kerchief is folded diagonally in two, then wrapped around the braids on the head so that the decorative corner hangs down behind, with the edge parallel to the floor, one end looped through the other and the whole thing pinned into place. The kothros has since been abandoned except for the village of Megala Kalyvia. This is why the headdress appears bulky in old photographs

Now the hair is separated into two halves, the left is braided behind the ear, then brought to the right side, and both parts are braided together, the braid is brought around the right ear and then over the top of the head. Hair extensions are added as needed. Hatzimichali gives a detailed description of this starting on pg 128. The method of wrapping is the same, but some areas tweak the process which results in distinctive local shapes.

Often a chain with attached coins is hooked to the front of this, and an ornament called kopitsa is hooked to the back. The Kopitsa varies somewhat in form.

Older women tie the kerchief under the chin and around the neck. They do not wear the kopitsa but often embroider the kerchief.

In both of the above images, the women are wearing black wool overgarments which are part of the winter costume and which I will not go into today, as they are somewhat complicated, in keeping with the rest of the costume.

A wide variety of jewelry is worn, in keeping with the occasion, as well as the status and age of the wearer. Many of these involve various pieces chained together. Peruse the various images of this article.

Thank you for reading, I hope that you have found this to be interesting and informative.

I will close with some more images of the costume of the Karagouni.

Traditional dance of the Karagounai.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OhRj_Spl-AQThe ritual final dressing of the bride followed by dancing

A long video showing a local festival in the Karagouna region

Feel free to contact me with requests for research. I hope to eventually cover all of Europe and the Former Russian Empire/Soviet Union. I also gratefully accept tips on source materials which i may not have. I also accept commissions to research/design, sew, and/or embroider costumes or other items for groups or individuals. I also choreograph and teach folk dance.

Roman K.

Source Material:

Angeliki Hatzimichali, 'The Greek Folk Costume vol 2', Athens, 1984

Ioanna Papantoniou, 'Greek Costumes', Nafplion, 1981

Popi Zori, 'Embroideries and Jewellery of Greek National Costumes', Athens, 1981

_Part3.jpg)

+%C2%ABTwo+women+in+winter+landscape+Valais%C2%BB.jpg)

\

\